Ink, Intention, and Everything in Between

I don’t always write with a fountain pen. Most days, it’s a keyboard and a blinking cursor, or a cheap ballpoint I grabbed from the bottom of my bag. But when I do reach for my fountain pen, something in me shifts. My posture changes. My breathing slows. It’s almost like lighting a candle before a conversation with myself. I’m declaring, quietly but firmly: this matters.

Let’s be honest: it’s also indulgent, and I love that. The pen itself is a little bit of theatre in my hand—sleek body, gleam of metal, nib poised like it has something important to say. The way the ink glides out—not rolled like a ballpoint but drawn through that tiny slit by capillary action—feels almost alive. A ballpoint just deposits ink; the fountain pen responds. If I tilt my wrist a little too far, the line thins and scratches; if I relax into the sweet spot, somewhere around a 45-degree angle, the line settles into a smooth, confident stroke. It’s a relationship, not just a tool.

I write for a living, or at least I write for a life that demands constant communication. Emails, documents, texts, notes to myself that I may or may not ever read again. I try to be intentional with my words, but there’s a gap between intention and impact. Ten years with a British partner in my twenties laced my vocabulary with “whilst” and “fortnight” and made me a bit precious about phrasing. I’ll catch myself reaching for a slightly more elaborate word than strictly necessary—half because it’s fun, half because it feels like a wink to that chapter of my life.

My handwriting, though, does not always rise to the occasion. When I redline a document my team has prepared, I start out like Dr. Jekyll: crisp, neat marginalia, each note clearly meant to guide, not confuse. Then the pace picks up, and Mr. Hyde arrives. The red ink becomes a frantic tangle of loops and slashes, and even I sometimes have to squint to decode what I thought was urgent at the time. The fountain pen exposes this split personality even more, because every stroke shows on the page—no disguising the chaos.

And yet, that’s part of why I reach for it. The fountain pen forces me to slow down. You can’t press too hard; you’ll bend the nib. You can’t rush; the ink will skip or pool. You have to find that exact angle where the nib kisses the paper and the ink flows easily, and then stay present enough to keep it there. Every letter becomes a tiny act of balance. Every word is a decision. I’m not just writing; I’m committing.

Of course, my romance with the fountain pen isn’t always graceful. Once, on a trip, I tossed my pen into my bag like it was any other pen. I didn’t think about pressure, or altitude, or anything as nerdy as air expansion. Somewhere between takeoff and landing, the air inside the pen decided it wanted more space. By the time I opened my bag in the hotel room, my “special” pen had expressed itself all over my life.

There it was: a dark, dramatic bloom of ink spreading through the lining of my bag, seeping into a notebook, staining the corner of a scarf I loved. The pen itself sat there, looking completely innocent, while the feed and nib were choked with ink that had been pushed out by the pressure change. I remember just standing over the mess, torn between horror and a weird, grudging admiration. Of course, my fountain pen didn’t just leak; it made a scene.

I cleaned it up as best I could, blotting, dabbing, muttering to myself. My fingers were stained for days, faint smudges of blue and black that clung to my cuticles no matter how much I scrubbed. Strangely, I didn’t hate it. It was like carrying a visible reminder on my hands that I had chosen this slightly extra, slightly complicated object. It came with consequences. It wasn’t neutral.

That’s the thing: using a fountain pen is never neutral for me. It’s a choice I feel every time I uncap it. Somewhere, in a subconscious hierarchy of importance, I must believe that what I’m about to write deserves this level of attention. That it deserves a tool that can’t just be tossed aside without leaving a mark.

My friend with a gift wrap room gets this on a level that makes me feel seen. She doesn’t just wrap presents; she curates them. She has drawers of tissue paper in different weights, shelves of wrapping paper organized by season and mood, ribbons that range from velvet to twine. Her tape is good tape—the kind that disappears into the fold, not the cheap kind that peels up at the corners.

When she wraps a gift, she’s fully inside that moment. She told me once that the whole process—choosing the paper, pairing it with the right ribbon, picking a card that says exactly what she means without saying too much—calms her. Shopping for cards and papers and little details gives her mind something gentle to hold. It pulls her away from the current anxieties—money, family, work—and into something she can control, shape, and finish.

People always comment on her wrapping. They’ll say, “This is too pretty to open,” and they mean it. They linger on the outside, turning the box in their hands, admiring the corners she’s folded so precisely. She always laughs and says, “Please open it, the real gift is inside,” but I know the wrapping is part of her gift. It’s her way of saying, “I thought about you long before this moment.”

That’s exactly how the fountain pen works for me. No one else may notice the slight shading in the ink where my stroke slowed down, or the way my letters open up more when I’m relaxed. No one else feels the tiny catch when I fall out of the nib’s sweet spot and then find it again. But I do. And somehow, that’s enough. It’s like I’m wrapping my own thoughts before I hand them to the world.

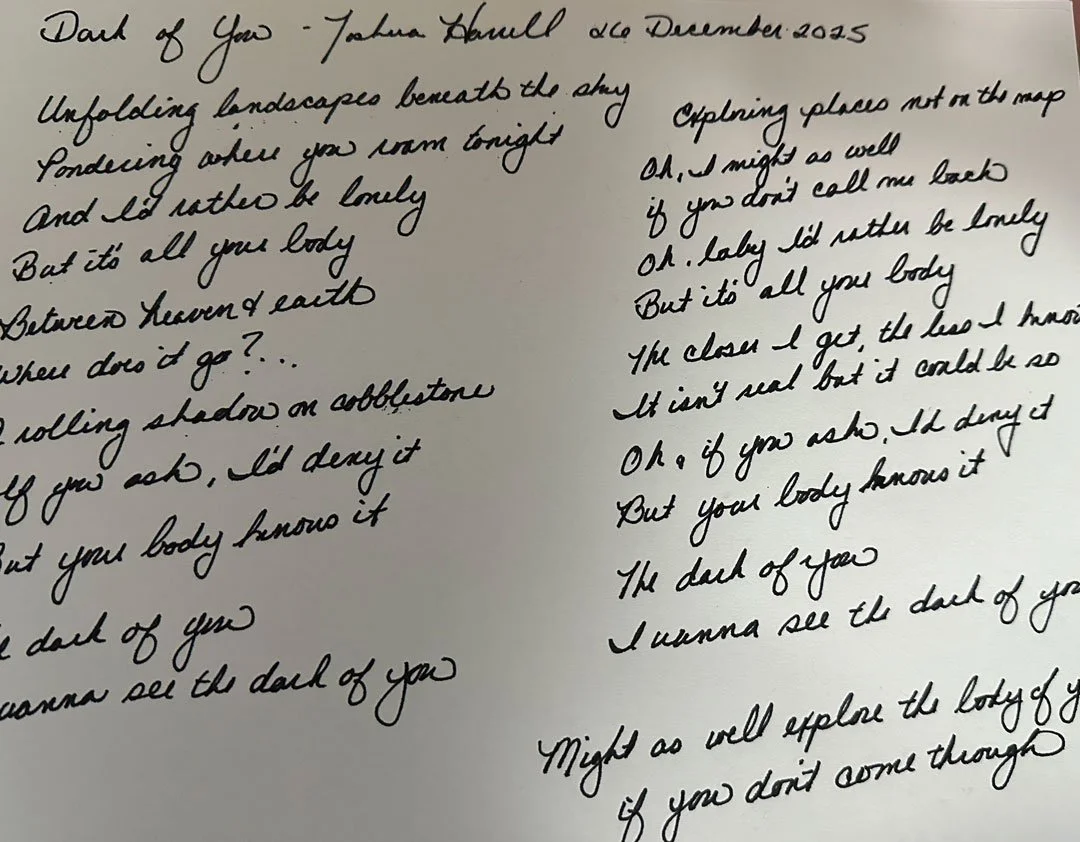

The same impulse shows up in my music. Turning fifty made something in me say, “Enough waiting.” I’d carried songs around in my head and my body for decades—half-finished melodies, phrases that had nowhere to land. Making an album felt at first like a milestone project, a way to mark a point in my life, but it turned into something more like a release.

In the studio, surrounded by cables and mics and the unnerving dryness of my own voice in the headphones, something miraculous happened: everything else disappeared. I wasn’t thinking about work or the next meeting, or the laundry waiting for me at home, or how much was in my bank account. I was thinking about pitch, rhythm, and whether that one line should land on the beat or just behind it. It was the same presence I feel when I’m watching ink move from nib to paper—absolute focus, but gentle.

Recording music has become my way of clearing out the mental clutter. It’s similar to how handwritten words feel different from typed ones. When I’m writing lyrics with my fountain pen, I’m aware of how each loop connects to the next, how I cross my “t,” how my “g” dips below the line. I think about how the letters themselves look like they’re holding the sound of the words. It’s not just content; it’s choreography.

I won’t pretend this is some noble pursuit. I’m also just having fun. There’s joy in choosing a deep blue ink instead of black, in watching it dry and shift slightly in tone, in feeling the tiniest bit fancy for no good reason. There’s joy in a ribbon that’s completely unnecessary but absolutely right, in a harmony that nobody asked for but I needed to hear. These small acts of excess make me feel more like myself, not less.

At the end of the day, I think we’re all quietly making choices about how much of ourselves we pour into what we do. Some people push their limits at the gym or chase new distances on their morning runs. Others bake, garden, build furniture, or spend a ridiculous amount of time perfecting a spreadsheet. Some don’t feel compelled to dive that deep into anything, and that’s okay, too.

But if you never let yourself get tucked into something—never let yourself care too much about a pen, a bow, a chord progression—you might miss the strange, beautiful way those obsessions expand you. For me, a leaking fountain pen, ink-stained fingers, a perfectly wrapped gift, a song that finally sounds the way it felt in my chest—these are all evidence that I’m still stretching. Still curious. Still willing to choose the slower, messier, more intentional way, just to see who I might become on the other side.